Does the Rattle Chapbook Prize live up to the hype? (Part 1) (Read Part 2)

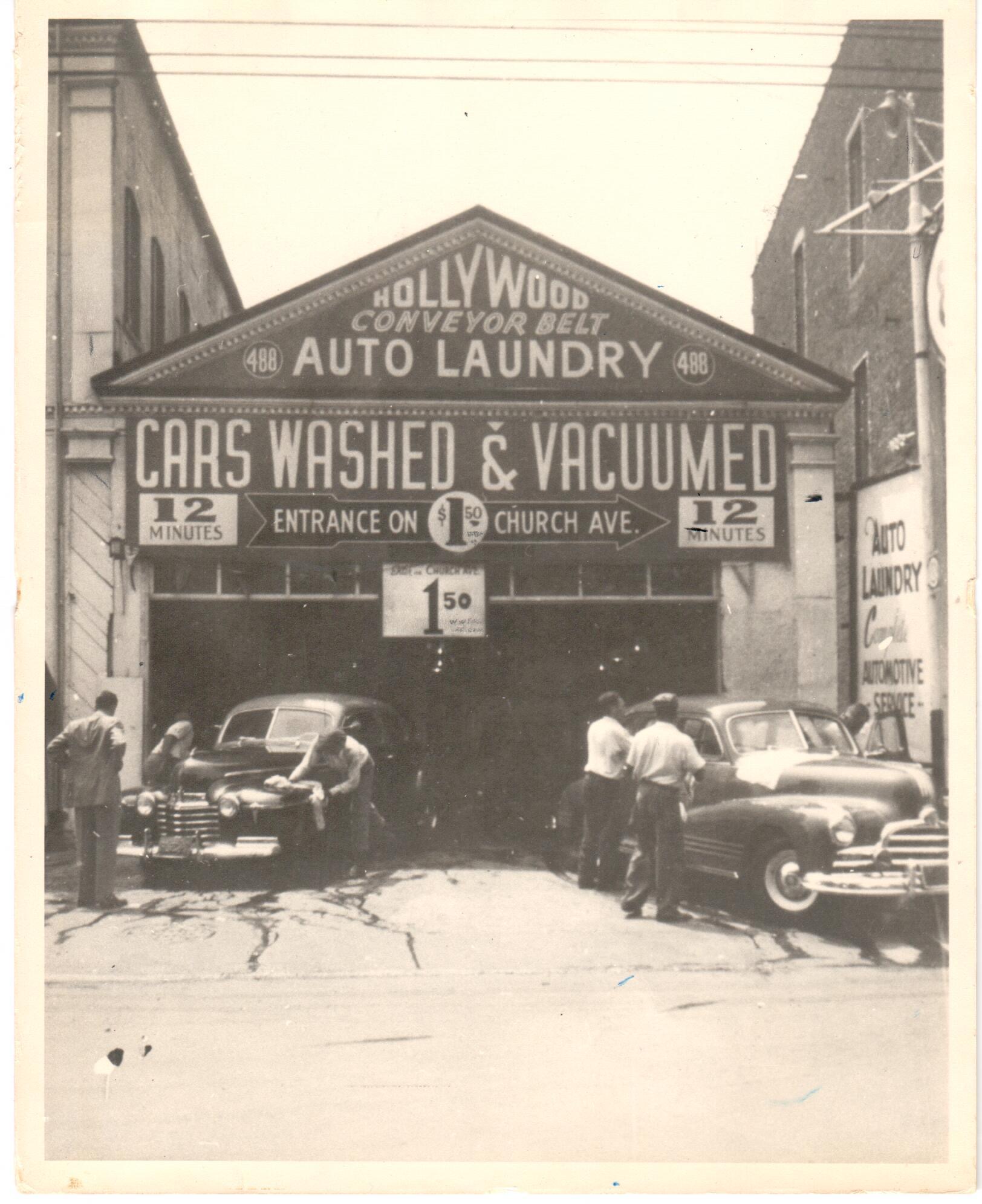

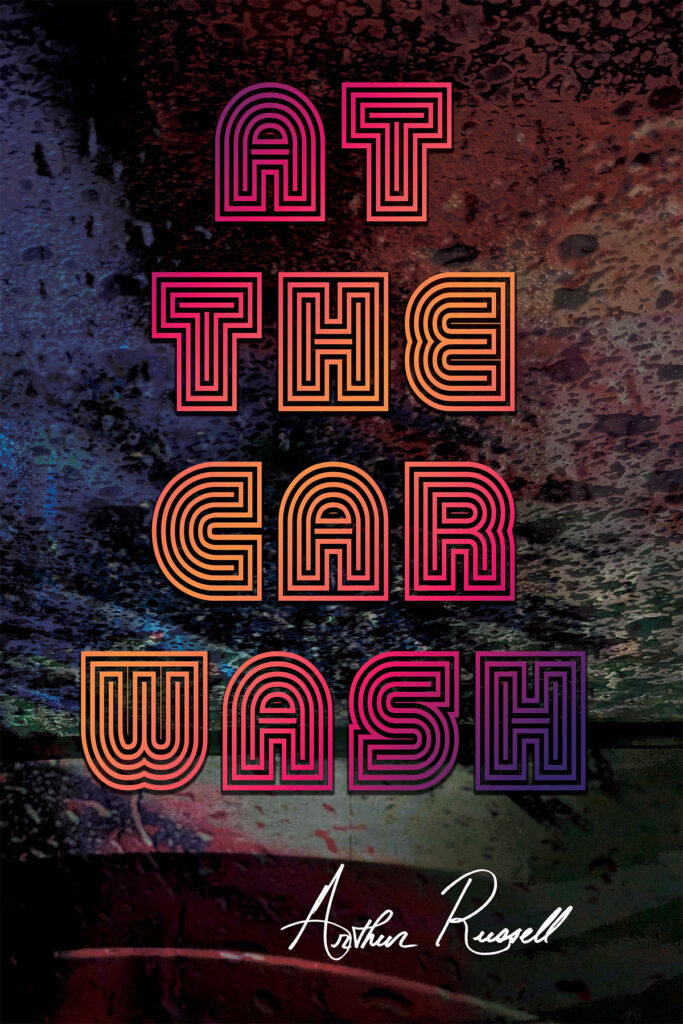

At the Car Wash

by Arthur Russell

Rattle Foundation, 48pp., $6.00 (print)

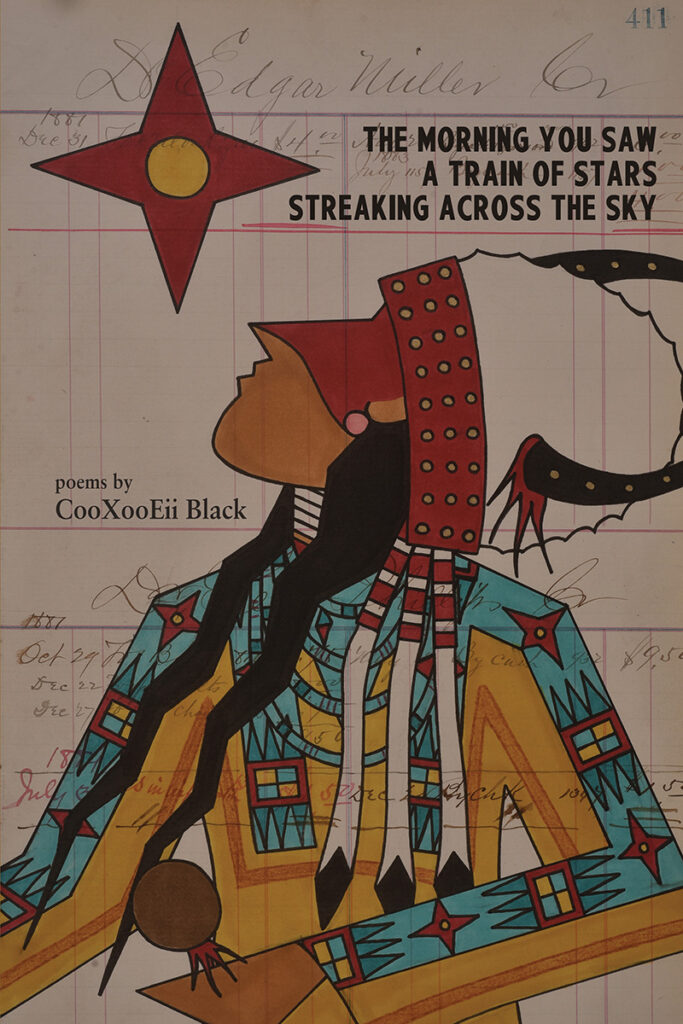

The Morning You Saw a Train of Stars Streaking Across the Sky

by CooXooEii Black

Rattle Foundation, 36pp., $6.00 (print)

One sunny day this past November, I opened the mailbox to find a shrink-wrapped copy of Rattle Magazine’s Fall 2023 issue, my first, along with Arthur Russell’s At the Car Wash. The nascent idea for the Philly Poetry Chapbook Review took shape, with the internet domain already reserved, and I requested two more recent titles. These would be the first chapbooks reviewed by PCR.

Last year, Russell’s chapbook won the Rattle Chapbook Prize, a contest held annually since 2016. Rattle Magazine is a product of the Rattle Foundation, whose goal is to promote the practice of poetry. I chose CooXooEii Black’s The Morning You Saw a Train of Stars Streaking Across the Sky and Amanda Newell’s I Will Pass Even to Acheron, winners in 2022 and 2021, respectively. Originally, I planned to write three independent reviews and publish them separately in PCR’s first three months. After I started looking for poetry books to review— and found more than I could ever hope to read— I decided to write a combined essay review of Russell’s and Black’s chapbooks. These two essays will seek to answer the question, “Does Rattle Magazine’s chapbook prize live up to the hype?” The second part reviewing Newell’s book will appear in early February.

I want to start with a clarification of this question. This essay is not a commentary on whether poets should enter the Rattle Chapbook Prize. Editor Timothy Green runs one of the more rewarding contests I’ve seen, with both significant cash prizes for winners and exposure by way of distribution to the magazine’s thousands of poetry-obsessed subscribers. If you want to enter a chapbook contest, and you have a great manuscript, this one’s a good choice. I’m also not interested in comparing the winners of other chapbook prizes with these books. While an article like that may have value for writers and readers, it doesn’t match the goal of this publication, which is to champion poets and poetry publishers. For me, the best way to champion something you believe in is to write about it critically, but fairly.

The real question I set out to answer is what kind of chapbooks the Rattle Chapbook Prize produces. It’s the type of question to which people assume the answer is “the best.” Why not do the work of literary criticism and leave off speculating, though? Long form reviews of recent winners seemed the best way to go. The contest has several winners each year. The three reviewed as representative are the ones that looked suited to my own tastes based on their descriptions.

My poetic journey began in 1980s Brooklyn, ensconced inside a Jewish-owned car wash. The Speaker who runs through many of the poems in At the Car Wash bears a strong resemblance to the poet. Readers see and hear him in various roles at his father’s business, from the boss’s kid in the lunchroom to a grown manager of men he once palled around with. Most of the poems in this collection focus on the people involved in keeping the car wash running. Unlike the campy 1970s comedy movie; however, the collection doesn’t focus on fun times. Instead, the poet examines the lives of the people who work at the car wash in all of their capitalist squalor.

The poems in The Morning You Saw a Train of Stars Streaking Across the Sky tell of contemporary life as a young NDN, or Native Indian. This is the first time I’ve encountered that abbreviation, which CooXooEii Black uses to describe his indigenous background. His poems invite the reader into a small corner of his life in that world of peoples whom previous generations called “Native Americans.” Like Russell’s collection, it’s clear that these poems draw heavily on the poet’s life.

CooXooEii (pronounced Jaw-kuh-hay) Black is an Afro-Indigenous writer and a member of the Northern Arapaho Tribe of Western Wyoming. He completed an MFA program at the University of Memphis last year. Black capped that achievement by having two of his new poems published by Poetry Magazine (Oct. ‘23). According to his LinkedIn page, The Morning You Saw… is about “childhood and maturation; about the reservation and land; about an uncle who becomes a teacher; about wrestling with identity and faith; about impressions.” The fiction aspect should be kept in mind, though, since he also says it’s a combination of truth and myth.

Russell, meanwhile, is an attorney and landlord in New Jersey, living in the Sheepshead Bay neighborhood of Brooklyn, New York. In a video of his joint launch with poet Lana Ayers on her YouTube channel, the poet tells of how the collection’s title comes from the title song for the movie Car Wash, a Richard Pryor comedy that came out in 1976. His family considered the movie blasphemous, Russell joked, because of how untrue it was. His poems often show the stark reality of exploitative working conditions.

On the first read, Russell’s collection brought to mind the work of the late novelist, Philip Roth, a favorite of mine. Though he had his personal faults, Roth possessed an uncanny ability to introduce my mind, rooted in a devout Irish Catholic upbringing, into his Jewish New Jersey world in a way that felt genuine. Great literature allows readers to immerse themselves in worlds alien to them, both historical and fictional, and feel like they’ve had an experience. Russell’s poems similarly bring readers into the Speaker’s world and give them that glimpse. We can feel the presence of the Speaker’s father, the owner of the carwash, in every poem. The complex relationship between businessman father and artistic son grows more tangled as the Speaker starts in the family business as a grunt, moves up to management with age (like it or not), and considers the exploitative nature of employment there retrospectively.

Or do the poems show the life of a hardworking dad who had his faults? Like Roth’s character and appeal, their import is ambiguous. As the son of the owner, the Speaker is able to see it from the side of both management and the workers. Russell’s collection wrestles with this ambiguity throughout.

Readers can experience an instant sense of familiarity with the Speaker and his coworkers, as seen in the first poem, “The Car Wash”:

and then, at the electric panel,

the knife switch took a palm to throw;

the sequence of circuit breakers, compressors

and fluorescents coming on satisfied the order

etched where habit met identity.

Alan went to hang his army field coat,

From the first mention of Alan, one of the employees, he feels like an familiar friend. Russell’s poems introduce various characters other than the Speaker and his family. Freddie Rogers in “Checkout Man” lives up to his title with style. Readers learn that he “could spin a damp towel on his finger / as if it were a terrycloth pizza, / take a quick drag off his Winston,” before excusing himself to go ‘check out’ a girl at the bus stop. After she comes and goes, he recovers his cigarette “and flips his spinning towel ahead / to land on the hood of the next car out.”

The poems in The Morning You Saw… also show daily life with all of its faults. Black’s Speaker is a young, male NDN living a reservation life. Unlike in Russell’s collection, though, the father is conspicuous for his absence. Black lets readers feel this lack through his relationship with his uncle, who tries to fill the paternal void. At least, the reader is led to believe that it is one uncle. While he does an excellent job of creating an amalgamated character, Black has said that these poems drew on memories with six different uncles, all of whom he views as father figures. This seems in keeping with the way he roots himself in his tribal identity as much as anything else; an identity where all are part of one family.

Black also pays tribute to the spiritual father figures in his life. He uses punctuation effectively in his poems, but eschews almost all capitalization. References to the three persons of the Christian god— God, the Father, Jesus Christ, and the Holy Ghost, as well as their pronouns— prove to be clear exceptions. Christianity plays an obvious role in the Speaker’s worldview and Black pays it this respect. Only one other word in the text is capitalized: the name of the titular character of “Thundersnow”, an NDN character of legend.

The collection’s seventh poem, “My Name Is Carved,” shows the blending of tribal and Christian identities from the title line, which continues:

on the palms of God.

a black tattoo under the burnished,

bronze skin of a chief, keeping watch

over His tribe.

Association of Christian missionaries with mistreatment of indigenous peoples has led some to repudiate the faith as imperialist. Others adopt Christianity and shed some or all of their tribal identity. Black walks a fine line with grace, his Speaker making clear that both spiritual and cultural identities can— and do— inhabit his one body and soul. Though he seems ambivalent about what this means for his life, as the poem continues,

what have i become

but a permanent reminder

of God’s mighty hand

like a rancher’s brand

For Russell, the family’s faith seems more rooted in the business. The poet explores this as he moves from the physical atmosphere and the people working there to the more personal themes of family and the owners’ relationship to the carwash. The ambiguities in his simple, straightforward language brings these to life through the haze of memory. However, the presence hanging over the collection (and the carwash), doesn’t come into focus until the third poem.

“How to Replace a Toilet” sets a clear tone from the first lines of its two-and-a-half pages:

First, have a father, one who owns a car wash

where he employs poor Black men,

preferably those who’ve come north in the Great Migration,

but any poor Black man will do,

The Speaker uses this facetious explanation and the instructions that follow to reflect on his father, a stand-in for Russell’s own, and the role the carwash played in his life and the lives of its employees. With an eye toward social justice in the present, the Speaker seems ambivalent about his familial nostalgia. Not all memories are pleasant. The owner’s reply to his son’s complaint of a badly broken toilet is to tell his son to fix it himself.

This poem sets a tone that persists. When the owner tells his son he’ll have to clean the men’s feces out by hand if he forgets to put a plank over the broken toilet, a reader might wonder, “If that’s how he treats his son, how does he treat his non-familial employees?” We see some of this in the following poems. Ambiguous feelings about the past permeate throughout in poems like “Plant Life,” a sly allusion to the similarities of plantation slavery and later exploitative hiring practices.

Black’s Speaker touches on the complexities of mixed heritage. In “Infiltrator”, he tells how his uncle can blend into the Native Indian, Latinx, and Black communities, depending on the season. This poem alludes to where his uncle went for five years that he was away. It also hints that he may relate to the Speaker’s absent father from experience:

5 years down in mexico, knew just enough spanish to make it

work. he said he fell in love. said he has a kid down

there. but i think he means he built something

that he loves. and after so many years of being

away, it wouldn’t make sense to return.

The uncle obviously cares for his nephew, but he has his own failings. The poem that gives Black’s collection its title is the only one that directly addresses the Speaker’s absent biological father. While recalling a hunting trip with his uncle, the third stanza begins, “he’s told you about your dad. / said he’s a cool dude. that they text from time to time”. Little else is said, but the Speaker makes clear that it was his uncle who served as father figure. Black used the combined memories with six uncles to create one unnamed character of depth.

The first poem, “My Uncle Asked”, sets the stage well, showing his uncle to be proud, but hungry for recognition. It continues the title line,

can you write about me?

tell your readers i was the last

ndn to stand on that rock before they blasted

crazy horse’s face into its cracks and flat slopes.

The poem goes on to boast of war scars, memorial bareback horse rides, and the athleticism of his youth. We also hear that the uncle’s youth involved causing trouble. Though it’s never made explicit what kind of trouble he got into, an impression is given in the second poem, “Low Gear”, which begins “my uncle was the best runner / on the reservation.” After some speculation about why he ran so much, lines toward the end intimate that it is serious:

someone said when you discover what he did,

how can you go back?

he thought if he ran fast enough

he could beat time itself,

The Speaker, his uncle, and the land, itself, are evoked in these lines.

Both poets effectively arranged their poems for narrative. I could feel the decades passing and the worldview of Russell’s Speaker evolving. In the beginning lines of a later poem in At the Car Wash, “The Heavier Stone,” the Speaker recounts his relationship with his father succinctly,

My dad died eight years ago.

our relationship has improved a lot since then.

He arrives unannounced in my poems,

I wondered at times if prose fiction would be a better form for these stories. Russell’s use of long lines and clear narrative might make a reader ask if poetry might be limiting. Poems like “The Whales Off Manhattan Beach” make a good argument for the use of verse. It tells of the Speaker caring for his father toward the very end of his life. While I think some of these poems would make great short fiction, Russell’s use of gentle metaphor, deft lineation, and the emotional heft in simple lines justify their form.

Two of Black’s poems mention Russian olive trees, placing the setting in the Western United States, where these trees flourish. While they can be nice to look at, according to the California Department of Fish and Wildlife website, “When Russian olive establishes in an area, it chokes out native plants and prevents them from re-establishing, and can be detrimental to the natural hydrology of riparian areas such as stream banks.” (emphasis mine) They seem like effective metaphors for white colonialist thinking toward NDN culture in the United States, ever present and always draining.

In a poem called “I Got a Sweet Rez Angel”, the second stanza begins with:

i like the way she spreads her wings

russian olive trees

overrunning my yard

the ones whose low limbs i rode like bulls

The epigraph to the poem reads “after Tampa Red,” the stage name of a 1930s Chicago Blues musician, Hudson Whittaker. Among his greatest hits is a song called, “Black Angel Blues”. Black’s sweet rez angel is everywhere on the reservation, the poem implies, like the blues. It overlooks the inhabitants as the invasive Russian olive overlooks all with its long, hanging limbs. The ambiguous nature of these trees, both comforting to the Speaker and invasive toward the land, adds to their import.

Not all of the poems in either collection stick to weighty topics. Poems like Russell’s “New Years Eve” recall fond memories of the Speaker’s mother when he was a child. Most of his poems use long, unmetered lines, but one, “Mom Would Be a Cardinal,” stands out for its seven syllable blank iambic lines. Asked about it by email, Russell told me that there was a cardinal in his backyard with a seven note song. In response to a Brooklyn Poets prompt to write about a person as an animal, Russell viewed his parents’ relationship through this avian lens. The seven syllable iambics imitate the cardinal’s song.

As mentioned, Black also uses music and visual art as inspiration in several of his poems. The end notes indicate that two of the poems— “Work” and “Trusty on a Mule”— are both ekphrastic poems. They describe Romare Beardon’s Factory Workers and a woodcut by Hale Woodruff, respectively. These poems show Black’s creative character to go along with his autobiographical poetry.

Key for both collections is the depth of their father figures. While Russell shows his poetic alter-ego’s father in what some might see as a negative light, the poet reminded readers at his launch event that memory isn’t so simple. He acknowledged that he portrays his father as a dominant person, but admits that after the manuscript for At The Car Wash had been accepted and everything was set, he “started to think about the limits of [his father’s] control, the limits to his ability to be king of the world that he created.”

Though I didn’t connect with every poem in The Morning You Saw a Train of Stars Streaking Across the Sky, Black’s verse brings his world to life for the reader. We can hear the uncle, asking to have his story told. We see the bloody nature of the circle of life for both canine birth and elk hunting in the poem, “Life / Death”. We feel the tension of reconciling mixed cultures into a unified identity throughout. The product is greater than a collection of lines; it’s an experience.

These collections might not be to every reader’s tastes, but both poets show vital combinations of skill and talent. I look forward to seeing more of their work in the future and would recommend both chapbooks. The Brooklyn car wash of Russell’s memory is a world I know I’ll be revisiting. Its depth of character, both in its people and its memories, leaves me wanting to look a little closer. Black’s poetic world is only beginning to expand and his collection is a promising start.

Reasonable people can, and often do, disagree on what makes poetry great. For me, the heart of poetry is communicating ideas and emotions that just wouldn’t move the reader in the same way as prose. By this simple measure, all three of the books reviewed in this essay succeed. There will be some chapbooks readers like more than others, but at only $6 per book (or free with magazine subscription), it’s a fair price for quality work. To answer the question posed at the beginning of this essay, the Rattle Chapbook Prize does live up to the hype. It’s a great source of quality poetry that benefits the poet, publisher, and readers. I know I’ll be renewing my magazine subscription for another year.

Read Does the Rattle Chapbook Prize Live Up to the Hype? (Part 2)

Author Bio

Aiden Hunt is a writer, journalist, poet and critic. He is the editor, creator, and publisher of the Philly Poetry Chapbook Review. Previously, Aiden covered cannabis policy and other related issues for magazines and websites. He also created two journalistic websites, the last of which was syndicated as authoritative content by Newstex and NewsBank.

You can find out more about him at PAidenHunt.com.

Sources:

CooXooEii Black LinkedIn

Russell and Ayers book launch

Arthur Russell on Rattlecast

At the Car Wash Product Page

The Morning You Saw a Train of Stars Streaking Across the Sky Product page

Contents

New Poetry Titles (1/2/24)

Preview new books from Michigan State University Press, Able Muse Press, and Farrar, Straus, and Giroux.

January ‘24: Welcome to Our Beginning

Welcome to the first issue of the Philly Poetry Chapbook Review, January/February 2024! Hear from our editor what we have in store for readers this issue.

New Poetry Titles (1/9/24)

Preview new poetry books from Seven Kitchens Press, Milkweed Editions, Bloodaxe Books, W. W. Norton, University of Pittsburgh Press, Phoneme Media, Coffeetown Books, Central Avenue Publishing, and Archipelago.

Father Figures: Books by Arthur Russell and CooXooEii Black

Aiden Hunt reviews Arthur Russell’s At the Car Wash and CooXooEii Black’s The Morning You Saw a Train of Stars Streaking Across the Sky in this essay, subtitled “Does the Rattle Chapbook Prize live up to the hype?”

New Poetry Titles (1/16/24)

Preview new poetry books from Milkweed Editions, Nightboat Books, Alice James Books, Phoneme Media, University of Arizona Press, The University Press of Kentucky, Madville Publishing, Clare Songbirds Publishing House and Tram Editons.

Chapbook Round-Up: Climate Crisis and Showbiz Blues

C.M. Crockford interviews poets Rae Armantrout, Justin Lacour, and James Croal Jackson and previews their recently published or forthcoming chapbooks.

New Poetry Titles (1/23/24)

Check out new poetry books published in English between 1/23 and 1/29 from Bottlecap Press, Stanchion Books, Graywolf Press, Milkweed Editions, Phoneme Media, Button Poetry, RIZE, Wayne State University Press, Carcanet Press, Fireside Industries and Texas Review Press.

Violence of Craft: Your Mouth is Moving Backwards by Juliet Cook

Contributor Mike Bagwell explores and reviews poet Juliet Cook’s new chapbook from Ethel Press, Your Mouth is Moving Backwards.

New Poetry Titles (1/30/24)

Check out new poetry books published in English between 1/30 and 2/5 from Scribner (Editor’s Pick), Texas Review Press, Bottlecap Press, Kith Books, Slant Books, University of Notre Dame Press, Knopf, Little, Brown and Company, Tupelo Press, LSU Press, Wesleyan University Press, Peepal Tree Press Ltd., Grayson Books and Sourcebooks.

Review: The Funny Thing About a Panic Attack by Ben Kassoy

Contributor Francesca Leader reviews Ben Kassoy’s debut chapbook from Bottlecap Press, The Funny Thing About a Panic Attack.

New Poetry Titles (2/6/24)

Check out new poetry books published in English between 2/6 and 2/13 from Wesleyan University Press, Belle Point Press, Bull City Press, Kith Books, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, Coffee House Press, New Directions, Nightboat Books, CavanKerry Press, University of Queensland Press, Green Writers Press, LSU Press, Haymarket Books, Button Poetry, The University of Kentucky Press, Mercer University Press, Knopf, Persea Books and Peepal Tree Press Ltd.

February ’24: Of Conferences and Contributors

A note from editor and publisher, Aiden Hunt, about the AWP Conference, re-opening submissions, and looking for more contributors.

New Poetry Titles (2/13/24)

Check out new poetry books published in English between 2/13 and 2/19 from Kith Books, GASHER Press, Querencia Press, Bottlecap Press, Alice James Books, Penguin Books, Seagull Books, Mad Creek, Wayne State University Press, Deep Vellum Publishing, University of Chicago Press, The Lilliput Press, Able Muse Press, Washington State University Press, University of New Mexico Press and Mosaic Press.

Of War’s Seductions & Consequences: A Chapbook Review

Aiden Hunt reviews Amanda Newell’s I Will Pass Even to Acheron in this essay, the second part of his essay, “Does the Rattle Chapbook Prize live up to the hype?”

New Poetry Titles (2/20/24)

Check out new poetry books for the week of 2/20 from Bottlecap Press, University of Arizona Press, Carnegie Mellon University Press, University of Alberta Press, Nightboat Books, Signature Books, Mosaic Press and Small Harbor Publishing.